Angular 2 is inspired by modern web standards, especially Web Components, which led to the adoption of some of the methods of content projection used there. In this article, we’ll look at them in the context of Angular 2 using the ng-content directive

Content projection is an important concept when developing user interfaces. It allows us to project pieces of content into different places of the user interface of our application. Web Components solve this problem with the content element. In AngularJS 1.x, it is implemented with the infamous transclusion.

Basic content projection in Angular 2

Let’s suppose we’re building a component called fancy-button. This component will use the standard HTML button element and add some extra behavior to it. Here is the definition of the fancy-button component:

@Component({

selector: 'fancy-button',

template: '<button>Click me</button>'

})

class FancyButton { … }

Inside of the @Component decorator, we set the inline template of the component together with its selector. Now, we can use the component with the following markup:

<fancy-button></fancy-button>

On the screen, we are going to see a standard HTML button that has a label with the content Click me. This is not a very flexible way to define reusable UI components. Most likely, the users of the fancy button will need to change the content of the label to something, depending on their application.

In AngularJS 1.x, we were able to achieve this result with ng-transclude:

// AngularJS 1.x example

app.directive('fancyButton', function () {

return {

restrict: 'E',

transclude: true,

template: '<button><ng-transclude></ng-transclude></button>'

};

});

In Angular 2, we have the ng-content element:

// dunebook4/ts/ng-content/app.ts

@Component({

selector: 'fancy-button',

template: '<button><ng-content></ng-content></button>'

})

class FancyButton { /* Extra behavior */ }

Now, we can pass custom content to the fancy button by executing this:

<fancy-button>Click <i>me</i> now!</fancy-button>

As a result, the content between the opening and the closing fancy-button tags will be placed where the ng-content directive resides.

Projecting multiple content chunks

Another typical use case of content projection is when we pass content to a custom Angular 2 component or AngularJS 1.x directive and we want different parts of this content to be projected to different locations in the template.

For instance, let’s suppose we have a panel component that has a title and a body:

<panel> <panel-title>Sample title</panel-title> <panel-content>Content</panel-content> </panel>

And we have the following template of our component:

<div class="panel"> <div class="panel-title"> <!-- Project the content of panel-title here --> </div> <div class="panel-content"> <!-- Project the content of panel-content here --> </div> </div>`

In AngularJS 1.5, we are able to do this using multi-slot transclusion, which was implemented in order to allow us to have a smoother transition to Angular 2. Let’s take a look at how we can proceed in Angular 2 in order to define such a panel component:

// dunebook4/ts/ng-content/app.ts

@Component({

selector: 'panel',

styles: [ … ],

template: `

<div class="panel">

<div class="panel-title">

<ng-content select="panel-title"></ng-content>

</div>

<div class="panel-content">

<ng-content select="panel-content"></ng-content>

</div>

</div>`

})

class Panel { }

We have already described the selector and styles properties, so let’s take a look at the component’s template. We have a div element with the panel class, which wraps the two nested div elements, respectively: one for the title of panel and one for the content of panel. In order to grab the content from the panel-title element and project it where the title of the panel is supposed to be in the rendered panel, we need to use the ng-content element with the selector attribute, which has the panel-title value. The value of the selector attribute is a CSS selector, which in this case is going to match all the panel-title elements that reside inside the target panel element. After this, ng-content will grab their content and set them as its own content.

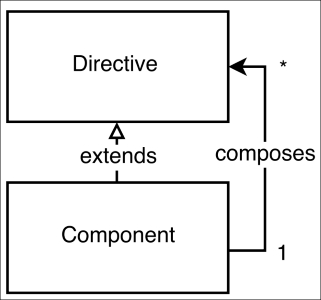

Nesting components

We’ve already built a few simple applications as a composition of components and directives. We saw that components are basically directives with views, so we can implement them by nesting/composing other directives and components. The following figure illustrates this with a structural diagram:

The composition could be achieved by nesting directives and components within the components’ templates, taking advantage of the nested nature of the used markup. For instance, let’s say we have a component with the

sample-component selector, which has the following definition:

@Component({

selector: 'sample-component',

template: '<view-child></view-child>'

})

class Sample {}

The template of the sample-component selector has a single child element with the tag name view-child.

On the other hand, we can use the sample-component selector inside the template of another component, and since it can be used as an element, we can nest other components or directives inside it:

<sample-component> <content-child1></content-child1> <content-child2></content-child2> </sample-component>

This way, the sample-component component has two different types of successors:

- The successor defined within its template.

- The successor that is passed as nested elements between its opening and closing tags.

In the context of Angular 2, the direct children elements defined within the component’s template are called view children and the ones nested between its opening and closing tags are called content children.

Using ViewChildren and ContentChildren

Let’s take a look at the implementation of the Tabs component, which uses the following structure:

<tabs (changed)="tabChanged($event)">

<tab-title>Tab 1</tab-title>

<tab-content>Content 1</tab-content>

<tab-title>Tab 2</tab-title>

<tab-content>Content 2</tab-content>

</tabs>

The preceding structure is composed of three components:

- The

Tabcomponent. - The

TabTitlecomponent. - The

TabContentcomponent.

Let’s look at the implementation of the TabTitle component:

@Component({

selector: 'tab-title',

styles: […],

template: `

<div class="tab-title" (click)="handleClick()">

<ng-content></ng-content>

</div>

`

})

class TabTitle {

tabSelected: EventEmitter<TabTitle> =

new EventEmitter<TabTitle>();

handleClick() {

this.tabSelected.emit(this);

}

}

There’s nothing new in this implementation. We define a TabTitle component, which has a single property called tabSelected. It is of the type EventEmitter and will be triggered once the user clicks on the tab title.

Now, let’s take a look at the TabContent component:

@Component({

selector: 'tab-content',

styles: […],

template: `

<div class="tab-content" [hidden]="!isActive">

<ng-content></ng-content>

</div>

`

})

class TabContent {

isActive: boolean = false;

}

This has an even simpler implementation—all we do is project the DOM passed to the tab-content element inside ng-content and hide it once the value of the isActive property becomes false.

The interesting part of the implementation is the Tabs component itself:

// dunebook4/ts/basic-tab-content-children/app.ts

@Component({

selector: 'tabs',

styles: […],

template: `

<div class="tab">

<div class="tab-nav">

<ng-content select="tab-title"></ng-content>

</div>

<ng-content select="tab-content"></ng-content>

</div>

`

})

class Tabs {

@Output('changed')

tabChanged: EventEmitter<number> = new EventEmitter<number>();

@ContentChildren(TabTitle)

tabTitles: QueryList<TabTitle>;

@ContentChildren(TabContent)

tabContents: QueryList<TabContent>;

active: number;

select(index: number) {…}

ngAfterViewInit() {…}

}

In this implementation, we have a decorator that we haven’t used yet—the @ContentChildren decorator. The @ContentChildren property decorator fetches the content children of the given component. This means that we can get references to all TabTitle and TabContent instances from within the instance of the Tabs component and get them in the order in which they are declared in the markup. There’s an alternative decorator called @ViewChildren, which fetches all the view children of the given element. Let’s take a look at the difference between them before we explain the implementation further

In next chapter you learn about .. ViewChild versus ContentChild